Sustainable management of transboundary rivers

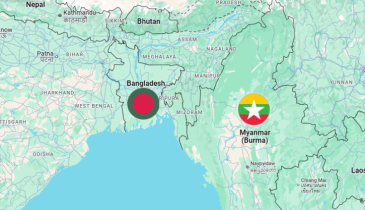

BANGLADESH is facing severe floods and river erosion due to irregular upstream water releases from barrages and dams on transboundary rivers. At the same time, excessive water withdrawal during the dry season is disrupting river ecosystems, leading to devastating impacts on agriculture and local livelihoods. This escalating crisis underscores the urgent need for a swift resolution to the long-standing water-sharing dispute and more effective transboundary river management strategies to prevent future catastrophes.

The people in the North Bengal districts Lalmonirhat, Kurigram, Nilphamari, Rangpur, Gaibandha and part of Mymensingh Division are now experiencing devastating flooding and river erosion as a result of the unusual upstream release of water from the Teesta River. The Teesta River, flowing through the Indian state of Sikkim and West Bengal before entering Bangladesh, has become a source of long-standing contention between India and Bangladesh. India constructed Gajoldoba Barrages and a dozen additional dams in the upper Teesta, putting Bangladesh at double risk. The Teesta mostly runs like a stream in Bangladesh during the lean period due to the withdrawal of water and overflows during the monsoon season due to abnormal releases, which cause flash floods in the region.

In July 2024, the country also experienced devastating floods in 11 eastern districts, such as Feni, Noakhali, Cumilla, Lakshmipur, Chattogram, Khagrachari, Sunamganj, Moulvibazar, and Habiganj, due to abnormal rainfall and releases of water from the Dumbur Dam on the Gomti River in Tripura, India. July floods also cause massive destruction of lives, livelihoods, livestock, and infrastructure. Agriculture has been severely hit, with nearly 297,000 hectares of cropland flooded, and the fisheries and livestock industries reporting combined losses of over $155 million.

Such flooding in different parts of the country during the wet seasons causes massive destruction of the lives and livelihoods of Bangladesh’s population and economy. According to a report released by the Centre for Climate Change Economics and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, 78 floods between 1971 and 2014 caused $12.2 billion in economic damages and killed over 41,783 lives in Bangladesh. It is projected that the flood of 2022 cost $1 billion and impacted 7.3 million people. Unfortunately, this has become a yearly phenomenon. However, it is most appropriate to say Bangladesh now experiences flooding whenever India chooses to open the gates of barrages or dams for discharging excessive amounts of water. Flooding in Bangladesh was a yearly occurrence until recently.

Even so, these risks are associated with climate change, which accelerates glacial melting, causes unpredictable rainfall patterns, and raises sea levels, but simultaneously the crises are worsened by state interventions. The indiscriminate construction of dams and barrages as well as artificial treatment to divert the flow of transboundary rivers in the upper streams on the Indian side is a common practice India has been doing over the years. The withdrawal of water during the dry season severely disrupts river ecosystems, including estuaries and adjacent marine areas. Reduced water flow causes rivers to dry up or lose depth, which has far-reaching consequences. One of the most critical impacts is on agriculture. According to the International Food Policy Research Institute, Bangladesh loses 1.5 million tonnes of boro rice annually, or 8.9 per cent of its total rice production, due to water shortages in the Teesta Barrage area.

During the wet season, when large volumes of water are suddenly released, the silted and shallow rivers are unable to contain the flow, resulting in flash floods. Districts near the Indian border are particularly vulnerable to these devastating floods. The continued mismanagement and aggressive release of river water by the upstream neighbour has been labelled as “water terrorism” by some observers. The failure to resolve the water-sharing issue has created friction between Bangladesh and India, straining an otherwise close relationship between the two South Asian neighbours. The rivers that both countries share play a crucial role in shaping the landscape, culture, and economy of the region. The rivers have huge implications for the lives and livelihood of more than 100 million people in different parts of Bangladesh, as well as the environment and biodiversity.

Given the current situation, it is crucial for Bangladesh to firmly demand its fair share of water and equitable treatment regarding transboundary rivers from the upper riparian countries. The unequal control over water resources is causing significant harm, destabilising the lives and livelihoods of millions in Bangladesh.

What are the solutions?

THERE are many dispute resolution mechanisms. The first stage is to negotiate bilaterally with the upstream countries. Secondly, third-party mediation and thirdly, arbitration by international courts of justice are the other techniques of resolving disputes. Numerous water disputes have been resolved through the involvement of third parties or international organisations. For instance, conflicts over the Jordan River were initially mediated by the United Nations and later by the United States. Similarly, the 1995 Mekong Agreement between Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam was facilitated by the United Nations Development Program, which established a framework for cooperation in managing the shared water resources of the Mekong River.

Despite a series of discussions and delegations that took place in recent years, it is clear that bilateral negotiations between Bangladesh and India have been in a stalemate for a long time. Bangladesh has been waiting for decades for a water-sharing treaty to be signed over the Teesta. The new interim government of Bangladesh recently stressed that the water-sharing dispute between the two nations should be settled in line with international standards. Given the situation, Bangladesh may consider taking USA-mediated third-party negotiations as the USA is actively engaged with both countries to ensure their regional presence in South Asia. But it is also important to involve the representatives from the Indian states of West Bengal and Tripura in the negotiation process, as the then chief minister of West Bengal objected fiercely when the Teesta water sharing deal was about to be signed during prime minister Manmohan Singh’s 2011 visit to Dhaka. This writing also advocates for the establishment of a joint river management system. This cooperative approach would ensure a continuous flow of water throughout the year, minimising the risk of ecological damage, agricultural losses, and human casualties. A major concern is the abrupt release of water, often without sufficient notice, leaving downstream populations with little time to evacuate or seek shelter. Bangladesh has repeatedly faced this issue, where water is released without prior warning or adequate communication, leading to catastrophic consequences. Joint management and timely communication are critical to address these recurring crises and prevent further devastation. Talks between the two countries take place following international guidelines so that a fair share can be achieved.

Alternatively, Bangladesh should prepare itself for taking the issue to the International Court of Justice. For that, Bangladesh first needs to sign the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, which forbids upper riparian countries from intervening in international rivers without the consent of the lower riparian countries.

Alongside international efforts to resolve the transboundary water crisis, the internal management of rivers and waterways in Bangladesh is equally critical. The country requires a massive overhaul to reclaim its rivers, canals, and waterways from illegal encroachment and pollution. Continuous efforts are needed to restore dried-up canals and conduct regular dredging to increase the depth of rivers, ensuring they can hold the maximum volume of water. This will enhance the capacity of the waterways, helping to mitigate flooding and improving water management overall. -Source:Newage

.png)