India, Globally: CAA, Manipur, and India's Human Rights Crisis

The Narendra Modi government frequently posits India as a ‘Vishwaguru’ or world leader. How the world sees India is often lost in this branding exercise.

Outside India, global voices are monitoring and critiquing human rights violations in India and the rise of Hindutva. We present here fortnightly highlights of what a range of actors – from UN experts and civil society groups to international media and parliamentarians of many countries – are saying about the state of India’s democracy.

International media reports-

The Economist: Tracing history and today’s context, the Economist published an explainer of Hindutva on March 7. Hindutva “seeks to equate Indianness with Hinduism.” While the BJP pushes “Hindu-nationalist priorities” such as the special status of Jammu and Kashmir and laws against cow slaughter and religious conversion, its critics say non-Hindu Muslims, especially Muslims, are being marginalised as “second-class citizens” and “Hindu-nationalist vigilante groups” are operating with impunity.

Reuters: Kanishka Singh reports on March 12 that in response to the Indian government’s notification of rules to enforce the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, a day before, the US State Department indicated that they will “closely monitor” its implementation and noted that “respect for religious freedom and equal treatment under the law for all communities are fundamental democratic principles”. The UN Office reiterated its view that the law is “fundamentally discriminatory in nature”.

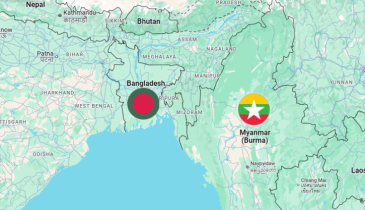

South China Morning Post: Amy Sood writes on March 12 that activists are alarmed at India’s move to deport thousands of refugees back to Myanmar, as the military there intensifies its fight against ethnic armed groups and pro-democracy rebels. Since Myanmar’s military coup in 2021, thousands of civilians and defecting Myanmar troops have taken shelter in the northeastern Indian states of Manipur and Mizoram through free movement policies at the border. Blaming the refugees for ongoing ethnic violence in Manipur, India is now reversing these policies. John Quinley III, Director of the international human rights group Fortify Rights, says “this is the worst time to send anyone back to Myanmar” and the decision to send them back “is against international human rights law”.

CBC News: Mark Gollom writes on March 13 that at the behest of the Indian government, YouTube has blocked access to a documentary by Fifth Estate, CBC’s documentary programme, on the fatal shooting of Hardeep Singh Nijjar last June. X (formerly Twitter) told CBC that it too has received a legal removal demand from the Indian government on the same story, but a decision has not yet been reached.

Le Monde: An investigative report by Sophie Landrin and Carole Dieterich published on March 13 focuses on noted human rights activist Harsh Mander and goes on to find that “under the impetus of the nationalist prime minister, the executive orchestrated a radical campaign against NGOs and human rights movements.” This “witch hunt” also spreads to the media and universities.

Parliamentarians advocate: Member of the House of Lords, Baroness D’Souza, on March 14, raised a question in the British Parliament under the title “Reported threats to democratic freedoms in India,” prompting strong debate. The Baroness said “the BJP policy of Hindu nationalism is increasingly invading press freedom, political opposition, and civil society space” and the use of anti-terror and sedition laws, among others “all hint at an electoral autocracy in the world’s largest nominal democracy”. Other peers questioned the British government on how it has been holding the Indian government to account on a range of topics including the situation in Manipur, violence against Christians and discrimination against Dalits.

Experts say

Volker Türk, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, said in a March 4 update to the UN Human Rights Council that he is concerned about the “restrictions on civic space, hate speech and discrimination against minorities, especially Muslims” in India as it heads to national elections this year.

Amnesty International released a statement on March 5 calling the “re-acquittal” of human rights defender G.N. Saibaba “a triumph of justice over continued repression.” It pointed to the “routine use” of the anti-terror law UAPA “as a tool to intimidate, harass and target activists like G.N. Saibaba” and called for “the immediate and unconditional release of all the other human rights defenders and activists” similarly “arbitrarily detained”.

A group of United Nations independent experts, part of the Special Procedures of the UN Human Rights Council, released a statement on March 7 raising their alarm that “attacks on minorities, media and civil society in India” are “likely to worsen” in the run-up to India’s impending national elections. They call on India to “fully” implement its human rights obligations and “reverse” the “erosion of human rights”.

The International Crisis Group released a commentary on the situation in Jammu and Kashmir on March 8, pointing to a “substantial gap” between the Indian government’s claims of “peace” and the actual situation on the ground. Militant activity has been pushed “deep underground” and “not a week goes by without an insurgent attack or a deadly encounter between insurgents and security forces”. It notes that many Kashmiris feel the Modi government has turned Kashmir into a “police state.” All political work is “severely curtailed” and journalists are being muzzled. The authorities must address the lack of voice in the region’s affairs including by holding elections.

Friends of Democracy, a new global effort to connect citizens concerned about the rise of authoritarianism around the world, hosted a conversation on March 9 between recently appointed upper house Member of Parliament (Trinamool Congress), and former journalist, Sagarika Ghose with Dr. Irfan Nooruddin of Georgetown University. In the context of Hindu nationalism, they discussed challenges facing Indian opposition leaders, including the use of anti-corruption tools to undermine Indian opposition.

Responding to the operationalization of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 2019, Amnesty International called it “a blow to the Indian constitutional values of equality and religious non-discrimination and inconsistent and incompatible with India’s international human rights obligations” in a March 14 statement. The government has failed to “listen to a multitude of voices critical of the CAA”. Amnesty notes that the CAA also expands the criteria for cancellation of the Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) registration as “another weapon” to “target and punish dissenting voices”. It demands the immediate repeal of the law.

A new book by Alpa Shah, Professor of Anthropology at the London School of Economics, titled The Incarcerations: Bhima Koregaon and the Search for Democracy in India alleges, on the basis of interviews with cyber security analysts, that evidence used to incarcerate 16 people in the Elgar Parishad case was “likely to have been implanted remotely through a hacker-for-hire mercenary gang infrastructure” and that an Investigating Officer on the case worked with the hackers to plant evidence in the computers of at least three of the accused.

Open Doors’ World Watch List 2024 ranked India as 11th in their latest annual ranking of the 50 countries where Christians face the most severe persecution. Published last month, the report terms anti-Christian persecution in India as “extreme”. It also highlights the targeting of Christians during the ethno-religious violence in Manipur as well as during mob attacks in Chhattisgarh, both in 2023.

The Pew Research Center recently released the findings of its survey on the popularity of representative democracy — and authoritarianism — around the world. Among its findings on India are that although people want democracy to be more representative, 82% said technocracy was at least somewhat good, 72% said military rule was at least somewhat good and 67% thought it was a good thing for a strong leader to be unconstrained by legislative or judicial interference. The share of the public that supports authoritarian systems was highest in India (85%) and lowest in Sweden (8%), the median being 31%.

The V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) Democracy Report 2024 observes that a “wave of autocratisation is observable globally”. India, with 18% of the world’s population, “accounts for about half of the population living in autocratising countries.” There has been sharp autocratisation in India from 2013, putting it at one of the top ten in recent times. It notes that India is no longer termed a democracy, but “dropped down to electoral autocracy in 2018” and remains there at the end of 2023. -Source: the wire

.png)